Intro to Automated Question Answering

A gentle introuction to QA systems, our new applied research project

- Question Answering in a Nutshell

- Why Question Answering?

- Designing a Question Answerer

- Building a Question-Answerer

Welcome to the first edition of the Cloudera Fast Forward blog on Natural Language Processing for Question Answering! Throughout this series, we’ll build a Question Answering (QA) system with off-the-shelf algorithms and libraries and blog about our process and what we find along the way. We hope to wind up with a beginning-to-end documentary that provides:

- insight into QA as a tool,

- useful context to make decisions for those who might build their own QA system,

- tips and tricks we pick up as we go, and

- sample code and commentary.

We’re trying a new thing here. In the past, we’ve documented our work in discrete reports at the end of our research process. We hope this new format suits the above goals and makes the topic more accessible, while ultimately being useful.

To kick off the series, this introductory post will discuss what QA is and isn’t, where this technology is being employed, and what techniques are used to accomplish this natural language task.

Question Answering in a Nutshell

Question Answering is a human-machine interaction to extract information from data using natural language queries. Machines do not inherently understand human languages any more than the average human understands machine language. A well-developed QA system bridges the gap between the two, allowing humans to extract knowledge from data in a way that is natural to us, i.e., asking questions.

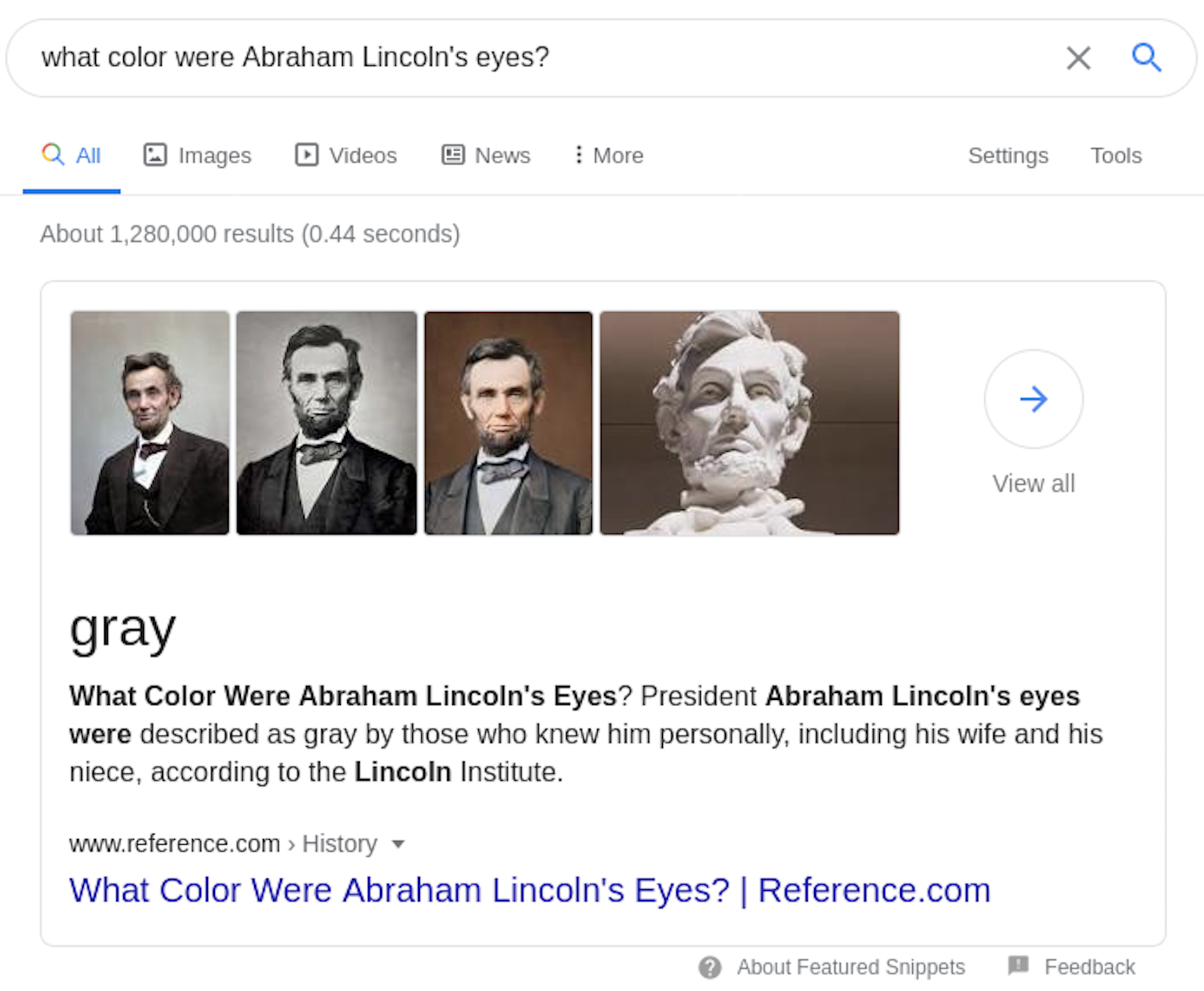

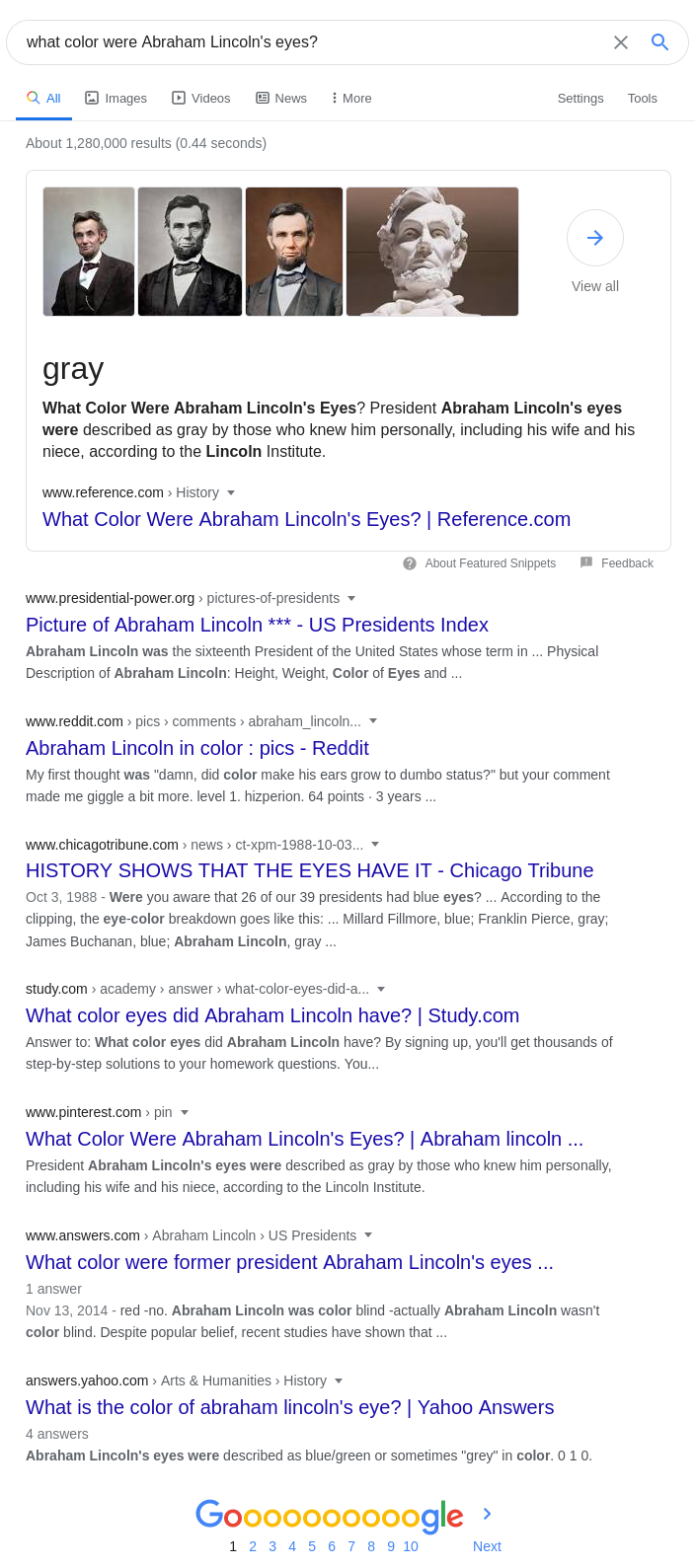

QA systems accept questions in the form of natural language (typically text based, although you are probably also familiar with systems that accept speech input, such as Amazon’s Alexa or Apple’s Siri), and output a concise answer. Google’s search engine product adds a form of question answering in addition to its traditional search results, as illustrated here:

Google took our question and returned a set of 1.3 million documents (not shown) relevant to the search terms, i.e., documents about Abraham Lincoln. Google also used what it knows about the contents of some of those documents to provide a “snippet” that answered our question in one word, presented above a link to the most pertinent website and keyword-highlighted text.

This goes beyond the standard capabilities of a search engine, which typically only return a list of relevant documents or websites. Google recently explained how they are using state-of-the-art NLP to enhance some of their search results. We’ll revisit this example in a later section and discuss how this technology works in practice and how we can (and will!) build our own QA system.

Why Question Answering?

Sophisticated Google searches with precise answers are fun, but how useful are QA systems in general? It turns out that this technology is maturing rapidly. Gartner recently identified natural language processing and conversational analytics as one of the top trends poised to make a substantial impact in the next three to five years. These technologies will provide increased data access, ease of use, and wider adoption of analytics platforms - especially to mainstream users. QA systems specifically will be a core part of the NLP suite, and are already seeing adoption in several areas.

Business Intelligence (BI) platforms are beginning to use Machine Learning (ML) to assist their users in exploring and analyzing their data through ML-augmented data preparation and insight generation. One of the key ways that ML is augmenting BI platforms is through the incorporation of natural language query functionality, which allows users to more easily query systems, and retrieve and visualize insights in a natural and user-friendly way, reducing the need for deep expertise in query languages, such as SQL.

Another area where QA systems will shine is in corporate and general use chatbots. Chatbots have been around for several years, but they mostly rely on hand-tailored responses. QA systems can augment this existing technology, providing a deeper understanding to improve user experience. For example, a QA system with knowledge of a company’s FAQs can streamline customer experience, while QA systems built atop internal company documentation could provide employees easier access to logs, reports, financial statements, or design docs.

The success of these systems will vary based on the use case, implementation, and richness of data. The field of QA is just starting to become commercially viable and it’s picking up speed. We think it’s a field worth exploring in order to understand what uses it might (and might not) have. So how does this technology work?

Designing a Question Answerer

As explained above, question answering systems process natural language queries and output concise answers. This general capability can be implemented in dozens of ways. How a QA system is designed depends, in large part, on three key elements: the knowledge provided to the system, the types of questions it can answer, and the structure of the data supporting the system.

Domain

QA systems operate within a domain, constrained by the data that is provided to them. The domain represents the embodiment of all the knowledge the system can know. There are two domain paradigms: open and closed. Closed domain systems are narrow in scope and focus on a specific topic or regime. Open domain systems are broad, answering general knowledge questions.

The BASEBALL system is an early example of a closed domain QA system. Built in the 1960s, it was limited to answering questions surrounding one year’s worth of baseball facts and statistics. Not only was this domain constrained to the topic of baseball, it was also constrained in the timeframe of data at its proverbial fingertips. A contemporary example of closed domain QA systems are those found in some BI applications. Generally, their domain is scoped to whatever data the user supplies, so they can only answer questions on the specific datasets to which they have access.

By contrast, open domain QA systems rely on knowledge supplied from vast resources - such as Wikipedia or the World Wide Web - to answer general knowledge questions. These systems can even answer general trivia. One example of such a system is IBM’s Watson, which won on Jeopardy! in 2011 (perhaps Watson was more of an Answer Questioner? We like jokes). Google’s QA capability as demonstrated above would also be considered open domain.

Question Type

Once you’ve decided the scope of knowledge your QA system will cover, you must also determine what types of questions it can answer. The vast majority of all QA systems answer factual questions: those that start with who, what, where, when, and how many. These types of questions tend to be straightforward enough for a machine to comprehend, and can be built directly atop structural databases or ontologies, as well as being extracted directly from unstructured text.

However, research is emerging that would allow QA systems to answer hypothetical questions, cause-effect questions, confirmation (yes/no) questions, and inferential questions (questions whose answers can be inferred from one or more pieces of evidence). Much of this research is still in its infancy, however, as the requisite natural language understanding is (for now) beyond the capabilities of most of today’s algorithms.

Implementation

There’s more than one way to cuddle a cat, as the saying goes. Question answering seeks to extract information from data and, generally speaking, data come in two broad formats: structured and unstructured. QA algorithms have been developed to harness the information from either paradigm: knowledge-based systems for structured data and information retrieval-based systems for unstructured (text) data. Some QA systems exploit a hybrid design that harvests information from both data types; IBM’s Watson is a famous example. In this section, we’ll highlight some of the most widely used techniques in each data regime - concentrating more on those for unstructured data, since this will be the focus of our applied research. Because we’ll be discussing explicit methods and techniques, the following sections are more technical. And we’ll note that, while we provide an overview here, an even more comprehensive discussion can be found in the Question Answering chapter of Jurafsky and Martin’s Speech and Language Processing (a highly accessible textbook).

Knowledge-Based Systems

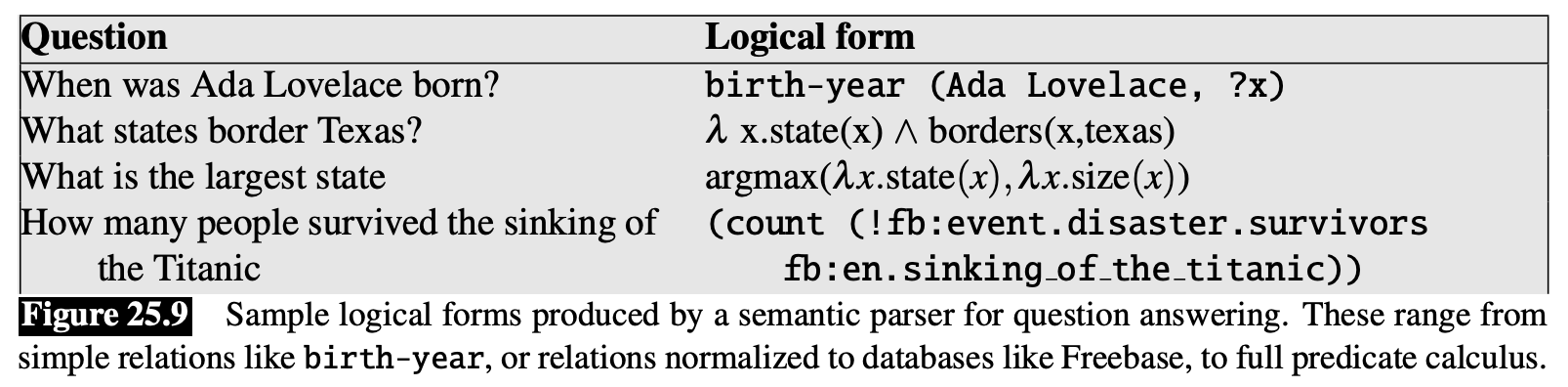

A large quantity of data is encapsulated in structured formats, e.g., relational databases. The goal of knowledge-based QA systems is to map questions to these structured entities through semantic parsing algorithms. Semantic parsing techniques convert text strings to symbolic logic or query languages, e.g., SQL.

Semantic parsing algorithms are highly tailored to their specific domain and database, and utilize templates as well as supervised learning approaches. Templates are handwritten rules, useful for frequently observed logical relationships. For example, an employee database might have a start-date template consisting of handwritten rules that search for when and hired since “when was Employee Name hired” would likely be a common query.

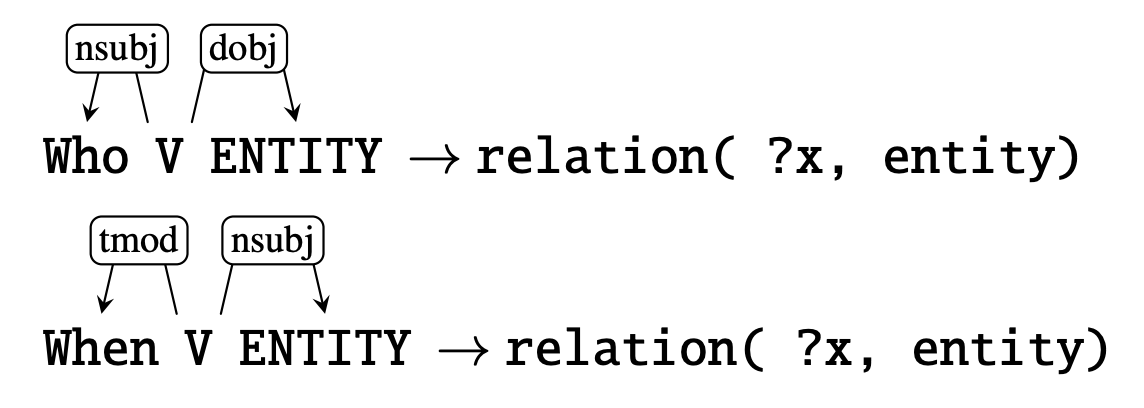

Supervised methods generalize this approach and are used when there exists a dataset of question-logical form pairs, such as in the figure above. These algorithms process the question, creating a parse tree that then maps the relevant parts of speech (nouns, verbs, and modifiers) to the appropriate logical form. Many algorithms begin with simple relationship mapping: matching segments from the question parse tree to a logical relation, as in the two examples below.

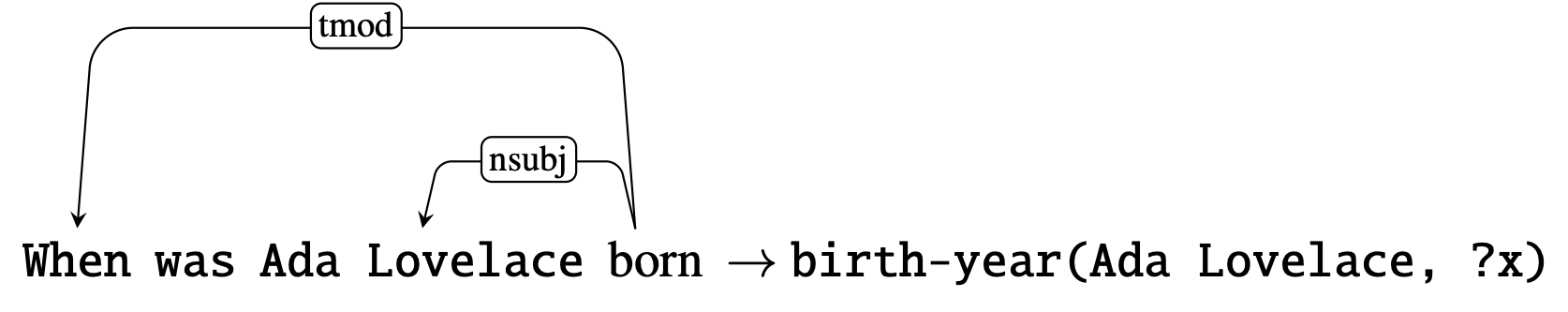

The algorithm then bootstraps from simple relationship logic to incorporate more specific information from the parse tree, mapping it to more sophisticated logical queries like this birth-year example below.

These systems can be made more robust by providing lexicons that capture the semantics and variations of natural language. For instance, in our employee database example, a question might contain the word “employed” rather than “hired,” but the intention is the same.

Information Retrieval-Based Systems: Retrievers and Readers

Information retrieval-based question answering (IR QA) systems find and extract a text segment from a large collection of documents. The collection can be as vast as the entire web (open domain) or as specific as a company’s Confluence documents (closed domain). Contemporary IR QA systems first identify the most relevant documents in the collection, and then extract the answer from the contents of those documents. To illustrate this approach, let’s revisit our Google example from the introduction, only this time we’ll include some of the search results!

We already talked about how the snippet box acts like a QA system. The search results below the snippet illustrate some of the reasons why an IR QA system can be more useful than a search engine alone. The relevant links vary from what is essentially advertising (study.com) to making fun of Lincoln’s ears (Reddit at its finest) to a discussion of color blindness (answers.com without the answer we want) to an article about all presidents’ eye colors (getting warmer, Chicago Tribune) to the very last link (answers.yahoo.com, which is on-topic - and narrowly scoped to Lincoln - but gives an ambiguous answer). Without the snippet box at the top, a user would have to skim each of these links to locate their answer - with varying degrees of success.

IR QA systems are not just search engines, which take general natural language terms and provide a list of relevant documents. IR QA systems perform an additional layer of processing on the most relevant documents to deliver a pointed answer, based on the contents of those documents (like the snippet box). While we won’t hazard a guess at exactly how Google extracted “gray” from these search results, we can examine how an IR QA system could exhibit similar functionality in a real world (e.g., non-Google) implementation.

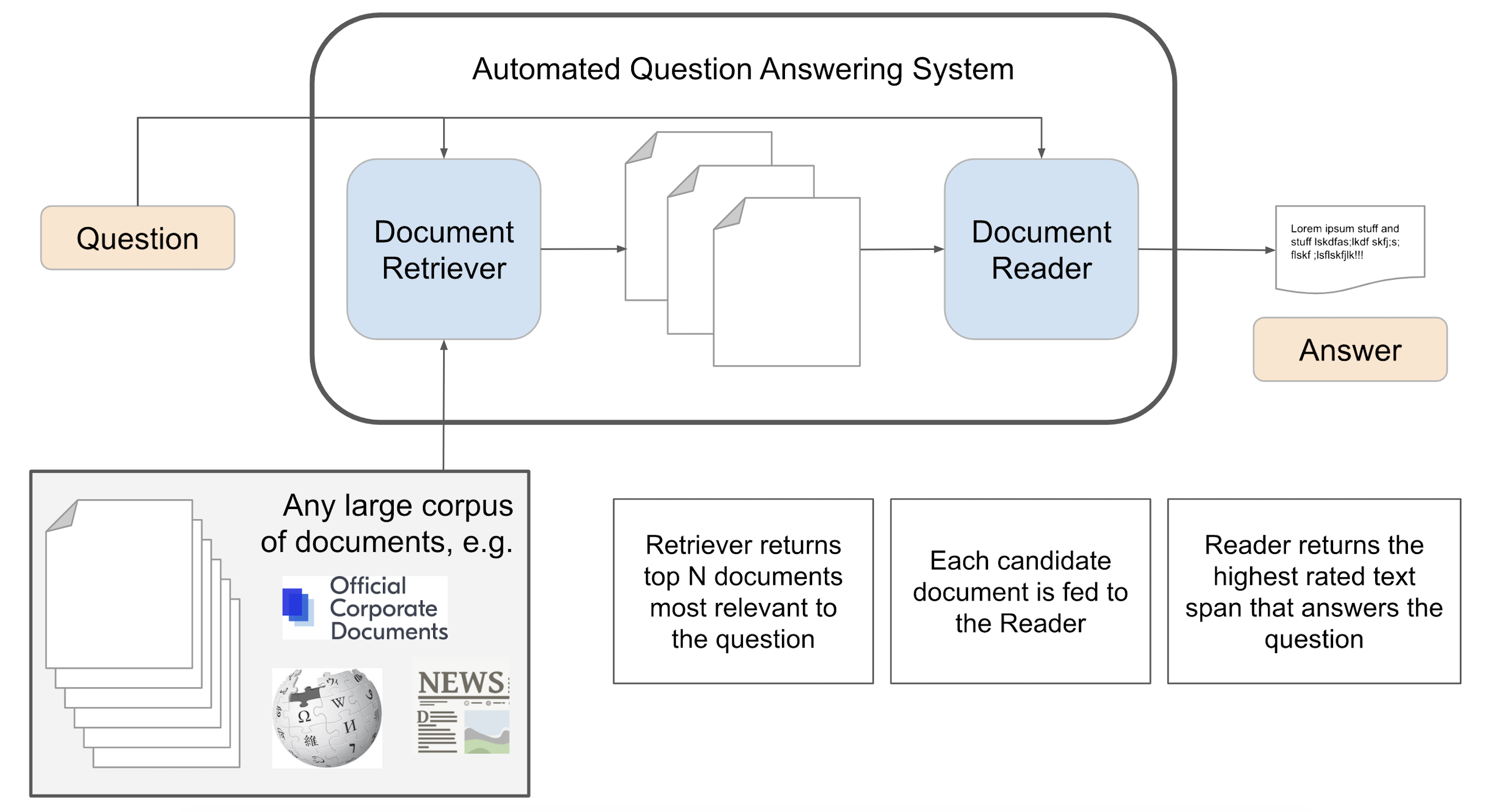

Below we illustrate the workflow of a generic IR-based QA system. These systems generally have two main components: the document retriever and the document reader.

The document retriever functions as the search engine, ranking and retrieving relevant documents to which it has access. It supplies a set of candidate documents that could answer the question (often with mixed results, per the Google search shown above). The document reader consists of reading comprehension algorithms built with core NLP techniques. This component processes the candidate documents and extracts from one of them an explicit span of text that best satisfies the query. Let’s dive deeper into each of these components.

Document Retriever

The document retriever has two core jobs: process the question for use in an IR engine, and use this IR query to retrieve the most appropriate documents and passages. Query processing can be as simple as no processing at all, and instead passing the entire question to the search engine. However, if the question is long or complicated, it often pays to process the query through various techniques - such as stop word removal, removing wh-words, converting to n-grams, or extracting named entities as keywords.

Some systems also extract contextual information from the query, e.g., the focus of the question and the expected answer type, which can then be used in the Document Reader during the answer extraction phase. The focus of a question is the string within the query that the user is looking to fill. The answer type is categorical, e.g., person, location, time, etc. In our earlier example, “when was Employee Name hired?”, the focus would be “when” and the answer type might be a numeric date-time.

The IR query is then passed to an IR algorithm. These algorithms search over all documents often using standard tf-idf cosine matching to rank documents by relevance. The simplest implementations would pass the top n most relevant documents to the document reader for answer extraction but this, too, can be made more sophisticated by breaking documents into their respective passages or paragraphs and filtering them (based on named entity matching or answer type, for example) to narrow down the number of passages sent to the document reader.

Document Reader

Once we have a selection of relevant documents or passages, it’s time to extract the answer. The sole purpose of the document reader is to apply reading comprehension algorithms to text segments for answer extraction. Modern reading comprehension algorithms come in two broad flavors: feature-based and neural-based.

Feature-based answer extraction can include rule-based templates, regex pattern matching, or a suite of NLP models (such as parts-of-speech tagging and named entity recognition) designed to identify features that will allow a supervised learning algorithm to determine whether a span of text contains the answer. One useful feature is the answer type identified by the document retriever during query processing. Other features could include the number of matched keywords in the question, the distance between the candidate answer and the query keywords, and the location of punctuation around the candidate answer. This type of QA works best when the answers are short and when the domain is narrow.

Neural-based reading comprehension approaches capitalize on the idea that the question and the answer are semantically similar. Rather than relying on keywords, these methods use extensive datasets that allow the model to learn semantic embeddings for the question and the passage. Similarity functions on these embeddings provide answer extraction.

Neural network models that perform well in this arena are Seq2Seq models and Transformers. (For a detailed dive into these architectures, interested readers should check out these excellent posts for Seq2Seq and Transformers.) The Transformer architecture in particular is currently revolutionizing the entire field of NLP. Models builts on this architecture include BERT (and its myriad off-shoots: RoBERTa, ALBERT, distilBERT, etc.), XLNet, GPT, T5, and more. These models - coupled with advances in compute power and transfer learning from massive unsupervised training sets - have started to outperform humans on some key NLP benchmarks, including question answering.

In this paradigm, one does not need to identify the answer type, the parts of speech, or the proper nouns. One need only feed the question and the passage into the model and wait for the answer. While this is an exciting development, it does have its drawbacks. When the model doesn’t work, it’s not always straightforward to identify the problem - and scaling these models is still a challenging prospect. These models generally perform better (according to your quantitative metric of choice) relative to the number of parameters they have (the more, the better), but the cost of inference also goes up - and with it, the difficulty of implementation in settings like federated learning scenarios or on mobile devices.

Building a Question-Answerer

At the beginning of this article, we said we were going to build a QA system. Now that we’ve covered some background, we can describe our approach. Over the course of the next two months, two of Cloudera Fast Forward’s Research Engineers, Melanie Beck and Ryan Micallef, will build a QA system following the information retrieval-based method, by creating a document retriever and document reader. We’ll focus our efforts on exploring and experimenting with various Transformer architectures (like BERT) for the document reader, as well as off-the-shelf search engine algorithms for the retriever. Neither of us has built a system like this before, so it’ll be a learning experience for everyone. And that’s precisely why we wanted to invite you along for the journey! We’ll share what we learn each step of the way by posting and discussing example code, in addition to articles covering topics like:

- existing QA training sets for Transformers and what you’ll need to develop your own

- how to evaluate the quality of a QA system - both the reader and retriever

- building a search engine over a large set of documents

- and more!

Because we’ll be writing about our work as we go, we might end up in some dead ends or run into some nasty bugs; such is the nature of research! When these things happen, we’ll share our thoughts on what worked, what didn’t, and why - but it’s important to note upfront that while we do have a solid goal in mind, the end product may turn out to be quite different than what we currently envision. Stay tuned; in our next post we’ll start digging into the nuts and bolts!